Tags:

Rebuilding the trust that the American people have in our government will require transforming public service delivery. This must include building a deep understanding of how individuals experience service journeys from their perspective, rather than our bureaucratic one. To effectively deliver public programs and services, they should be designed and delivered in a way that is intuitive, accessible, and responsive.

Imagine if the U.S. government understood how each of its services were part of a broader customer journey. How might Federal agencies change their approach or even work together? How might citizens think differently about those services and their overall experience with government?

A journey is one way to look at an experience and tell a story. Many in the private (and now public) sector use a process of “journey mapping” to provide multiple stakeholders with a common understanding of how a customer interacts with a service. You may have heard of tools like “user personas,” “customer maps,” “user journeys,” “behavioral maps,” “service blueprints,” and more.

Our team believes deeply in these processes to build shared knowledge of customer needs, using a physical artifact to ground conversations about improvements and priorities. These journeys can be mapped at all kinds of levels— from a specific interaction visiting a service center to change your name and apply for a new Social Security card, to an individual’s overall lifetime experience interacting with the Social Security Administration.

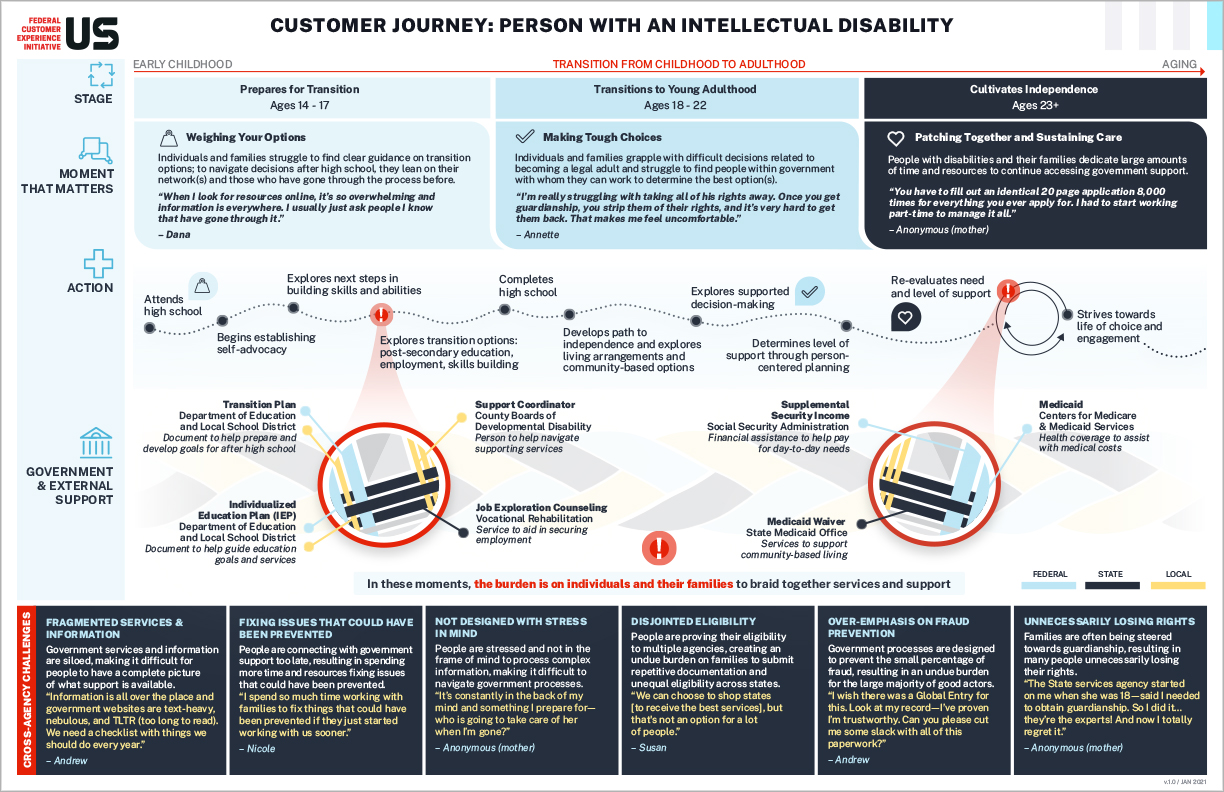

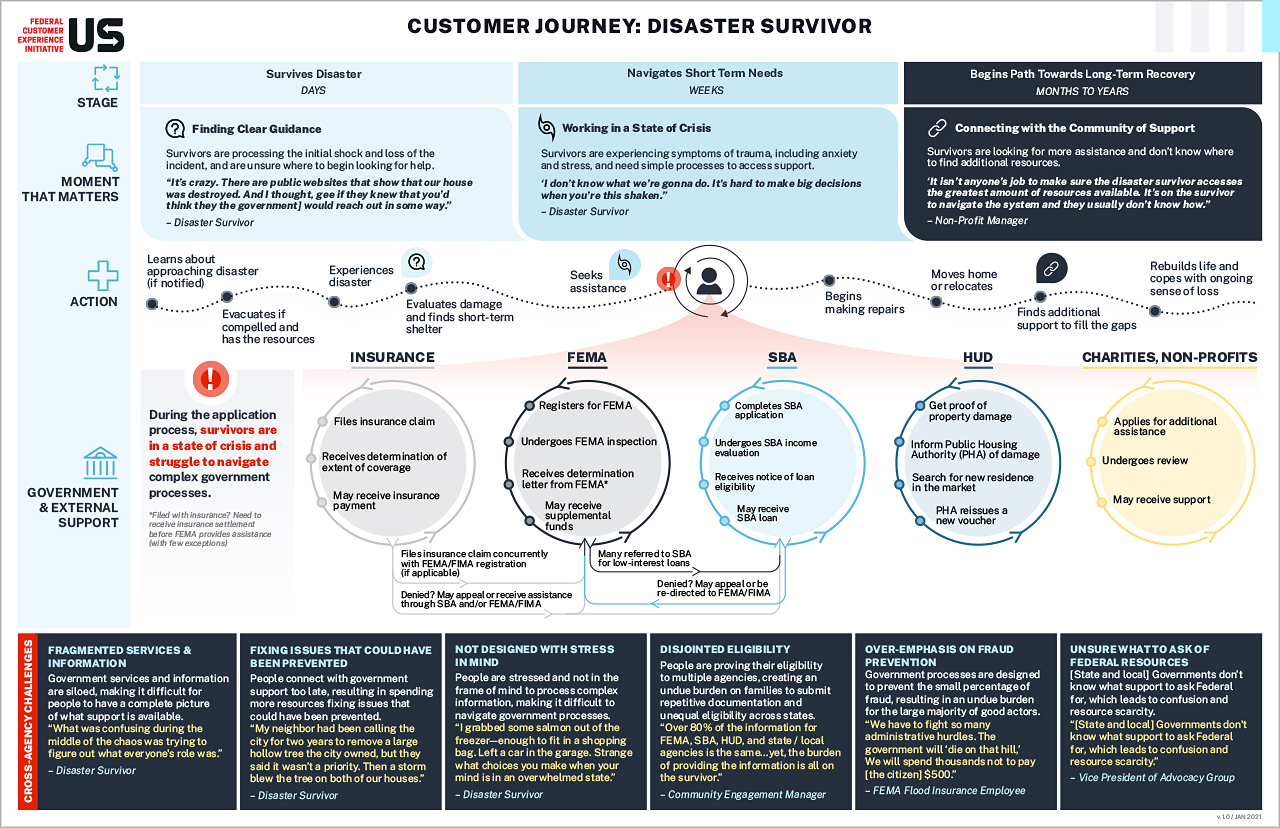

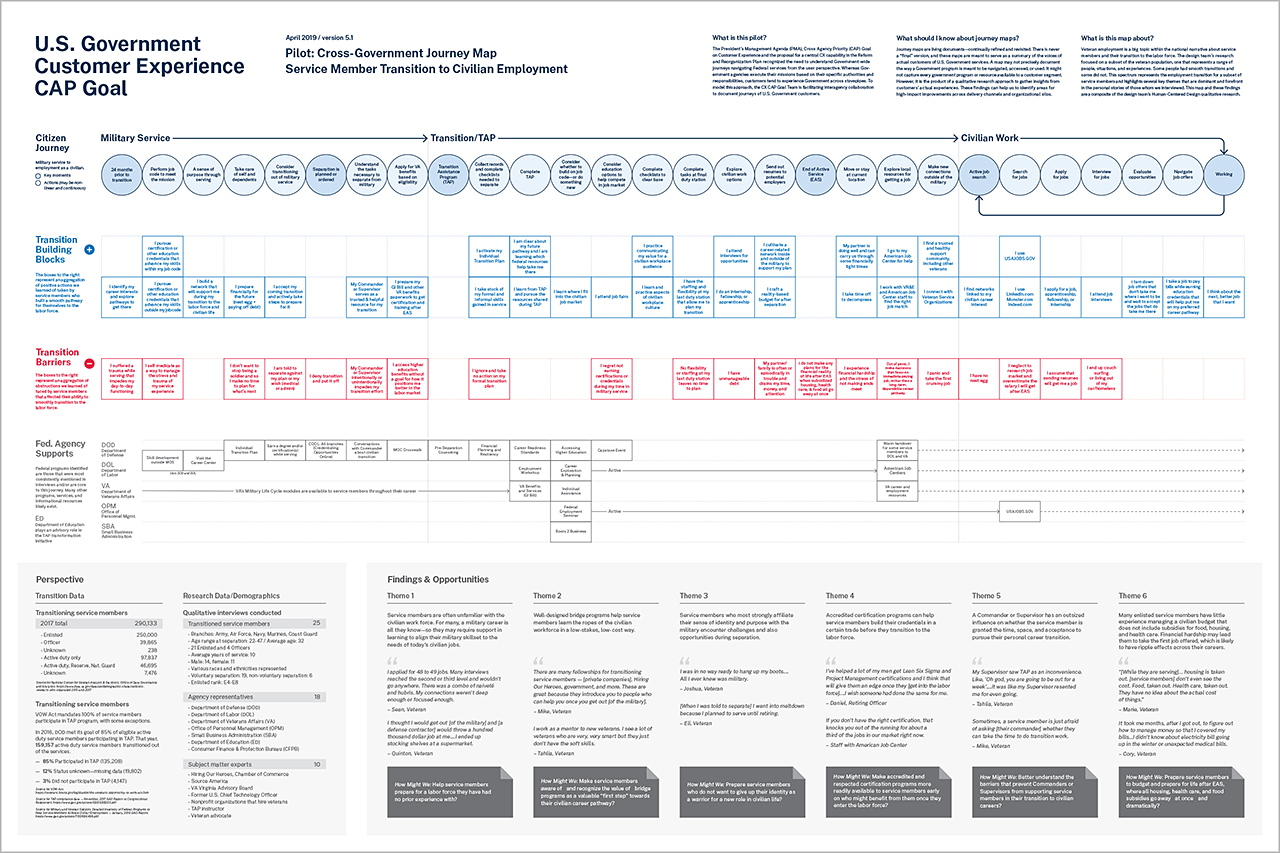

To begin to build further understanding of the individuals that we serve, the Federal Customer Experience Initiative (FCXI) team at the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) collaborated with civil servants representing more than a dozen Federal agencies to develop three customer journey maps.

We conducted more than 150 interviews of service members and veterans, persons with a disability, their family members, disaster survivors, advocacy and non-profit organizations’ representatives, case managers, service providers, and government employees at Federal, State and local levels. We also designed and deployed surveys of the disaster and disability customer communities, and collected over 350 survey responses.

Our objective was to model what it would be like to take this human-centered approach with agencies across government, orienting around individuals that we all serve. Through this effort, many civil servants conducted human-centered design research methods for the first time, were able to collaborate and meet colleagues that work in similar areas across government, and identify specific bottlenecks that are meaningful to real people, for us to focus our improvement efforts. Many of our collaborators have already begun using the insights they learned from these projects, applying the methods we used in other areas of their work, and are working with us on forming multi-disciplinary and multi-agency teams to continue this design process in challenge areas identified.

Creating a “Cross-Agency” Customer Journey Map

The OMB team facilitated interagency teams with collaborating partners from multiple Federal agencies:

Office of Management and Budget

General Services Administration

Department of Defense

Agency partners provided valuable input throughout the process, from meeting weekly to connect our design teams with experts at their agencies, providing context to what was being heard in interviews, drafting content and designing wireframes, to creating the initial design and personas, to redesigning and survey analysis, to developing the final products. For the disaster journey alone, we had sessions with 21 different people from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

It is important to note that agency partners may have drawn these journey maps differently on their own, or may see omissions in maps like these. However, the visuals created are drawn from the customer’s eyes. It reflects what actual people we talked to experienced, how they think and feel about what they experienced, and the resources they used or remembered along the way. It focuses not on what Federal agencies do on paper, but what resonates for the public in reality.

Building More Detailed Service Blueprints

Further efforts can be completed to build out more detailed “maps” of Federal services. It is important to capture both the front stage experience (what customers see) and the backstage operations (what makes this experience possible). For example, mapping efforts can include gathering:

- Qualitative Customer Data: From customer feedback surveys instrumented at each interaction or transaction to extensive, representative interviews across the country, the purpose of this data is to hear directly from people served in their own words. This data provides an understanding of what customers want, expect, and need from a system, product, or experience. Qualitative interviews shed light on how people see the world—their beliefs, mindsets, and how they think about the problem—and can help providers better understand what else is influencing how customers experience their service.

- Process Flows: During this step-by-step mapping, actions taken by customers, employees, or other entities involved in services being acquired or delivered can be documented. Especially when processes involve handoffs or multiple teams in service delivery, it is critical to ensure every step is captured accurately, checking assumptions we make about others’ roles. When completing specific service maps, employee processes and actions are as important to capture as front-facing customer steps.

- Rigorous Research and Behavioral Data: Sometimes what people say and what they do are entirely different things. This is where it is critical to have an understanding of behavioral science insights, or knowledge of how people access, process, and act on information. Environmental factors, such as how forms are structured or who is relaying information, can affect how individuals respond. Conducting literature reviews related to particular choke points in a system or finding rigorous evaluations of similar challenges can help add evidence-based insights.

- Operational Performance Data: Understanding how a process works at the nuts and bolts level is vital. Performance metrics such as application processing volumes, engagement on various channel types, key performance indicators, service level agreements, and cost per transaction provide important information about what is actually happening with customers and within the organization. A provider may hypothesize what a customer group finds confusing about a federal benefit program. Yet when they review data on actual customer questions, they may find more individuals are actually seeking information to address a different issue.

Together, these layers can build a more accurate picture of what matters most to customers, what drives the outcome of an organization’s mission, and where there is potential for a return on investment.

Government-wide Experience Lessons Learned

Our team attempted to incorporate data from each of the layers described above, focusing primarily on the first–qualitative customer data. Based on our design workshops, focus groups, interviews and surveys to produce these maps, we identified six insights that apply in multiple customer experiences interacting with government, some elements of which we also discussed in 2018.

- Government services and information are siloed in discrete agencies across the Federal government, and also at the state and local levels, a distinction that is meaningless to an individual trying to address a need. This can also make it difficult for people to have a complete picture of what support is available.

“When I look for resources online, it’s so overwhelming and information is everywhere. I usually just ask people I know that have gone through it.” – Dana

- Frequently, individuals connect with government supports later in a journey, resulting in costly and time-consuming remediation instead of lower-cost prevention or more proactive connection to supports that can help earlier.

“If you haven’t had the time to prepare… and then you are taking TAP [Transition Assistance Program], say a few months before you get out, you are just in a panic, and you are just thinking about getting a job, as a stop-gap, even though it may help you in the short run, but not in the long run.” – Maggie, Veteran

- Government services are not designed to account for the stress that many individuals are experiencing at the moments they interact. Especially when people in a moment in which they feel overwhelmed, government has an obligation to design information and services in ways that are easy to access and understand.

“I don’t know what we’re gonna do. It’s hard to make big decisions when you’re this shaken.” – Disaster Survivor

- Repetitive documentation generates burden and even increased costs. Often, this is because one Federal agency lacks access to information already submitted to a different Federal, State, or local entity. This is often amplified when programs require re-certifications or eligibility checks at different times.

“We need a Global entry for government services. Cut us some slack; don’t make use jump through hoops.” – Caregiver for a person with a disability

- A culture (and many would argue incentive structure) the puts the largest emphasis on fraud prevention often creates unnecessary hurdles that prevent honest applicants from receiving the services for which they qualify.

“People spend money to fight administrative hurdles. Private industry will just pay the thing to keep you happy. We will spend thousands to not pay the $500.00! We will die on that hill.” – Federal Agency Representative

- Trusted and informed guidance for navigating the labyrinth of Federal, state, and local government services is hard to find. As a result, some state and local governments do not know what support they should seek from the Federal government (or opportunities that exist to collaborate), and some individuals and families receive bad advice that results in government failing to provide them the benefits for which they are eligible—or even unnecessarily depriving them of their rights.

“Parents were told they could not be at the meetings unless they established guardianship. This was not true. An attorney drafted a sample legal letter that said this was IDEA compliant, in legal-eze and it scared parents. So, we reworded the letter, clarifying that parents could still be part of the meeting. It totally changed the flavor across the state.” – Doctor and Disability Advocate

What’s next?

Dedicated Federal employees work each day for the people that they serve-while many do their best to collaborate, and often provide good service within their silo, we know customers are frustrated with gaps created by our organizational lines. People experience life events, not Federal agencies. Customer needs should shape and determine public services. However, since Congress funds agencies, not life events, it is our responsibility to implement coordinated services that bridge that gap. Otherwise, we risk failing to achieve the very mission we are expected to deliver.

While spotting insights consistent across interviews and surveys is a beginning, and adding further data to build more robust service blueprints can help pinpoint areas for improvement, empathic human-centered service design requires more—specifically, that we involve the very people these programs are intended to serve in the development of solutions and redesign of our systems.

We are working to use our research as a launch point for collaborative efforts to address the challenge areas identified, so that multiple experiences with government can be improved. A government that actively and regularly listens, seeks to understand and involve the people it serves, and harnesses these insights to remove barriers to delivering the services it has promised, is one that can earn back the trust of the American public.